"If the Mississippi River changes its course during a major flood, it would be a disaster for shipping and economic impacts in New Orleans and the lower end of the waterway," AccuWeather Senior Meteorologist Alex Sosnowski said. This Aug. 2, 2018, file photo shows the Old River Control Structure

Old River Control Structure

The Old River Control Structure is a floodgate system in a branch of the Mississippi River in central Louisiana. It regulates the flow of water leaving the Mississippi into the Atchafalaya River, thereby preventing the Mississippi river from changing course. Completed in 1963, the comple…

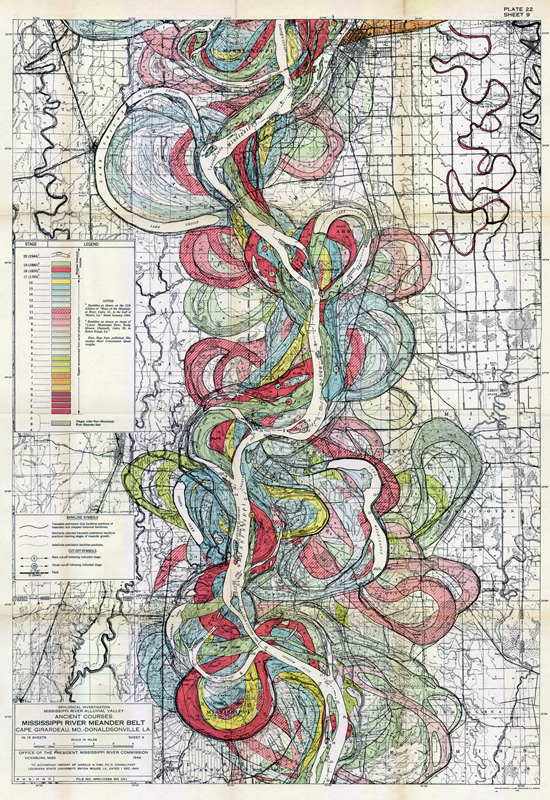

How did the Mississippi River course has changed over time?

Through a natural process known as avulsion or delta switching, the lower Mississippi River has shifted its final course to the mouth of the Gulf of Mexico every thousand years or so. This occurs because the deposits of silt and sediment begin to clog its channel, raising the river's level and causing it to eventually find a steeper, more direct route to the Gulf of Mexico.

What are facts about the Mississippi River?

⛵ 17 Fun Facts about The Mississippi River 1. It goes further than you might think. The Mississippi River actually flows more than 2,350 miles along, starting in... 2. It competes with the world’s longest rivers. The Mississippi River is actually one of the longest rivers on a global... 3. It’s a ...

Could the Mississippi River change course?

There are several factors that contribute to the change in courses of the Mississippi River. The main factor is energy. The Mississippi is a very curvy, knowns as meandering, river.

Where does the Mississippi River start and end map?

Where does the Mississippi River start and end? The Mississippi River rises in Lake Itasca in Minnesota and ends in the Gulf of Mexico. It covers a total distance of 2,340 miles (3,766 km) from its source. The Mississippi River is the longest river of North America.

See more

What would happen if the Mississippi river changed course?

"If the Mississippi River changes its course during a major flood, it would be a disaster for shipping and economic impacts in New Orleans and the lower end of the waterway," AccuWeather Senior Meteorologist Alex Sosnowski said.

When was the last time the Mississippi river changed course?

Many of these abandoned meanders provide important marshland wildlife habitat. The last major change to the river's course in the Vicksburg area occurred in 1876. On April 26 of that year, the Mississippi River suddenly changed courses, leaving Vicksburg high and dry.

How many times has the Mississippi river changed its course?

The Louisiana coast has been built over the last 7,000 years by the Mississippi River changing course and creating six different delta complexes. Before the extensive levee system that “trained” our river to stay in one place, the Mississippi changed course about once every 1,000 years.

Why did the Mississippi river change course?

The Mississippi River has changed course to the Gulf every thousand years or so for about the last 10,000 years. Gravity finds a shorter, steeper path to the Gulf when sediments deposited by the river make the old path higher and flatter. It's ready to change course again.

How far up the Mississippi can ships go?

Cargo Ship Comparison The change has East Coast and Gulf Coast ports increasing the depth of their terminals to 50 feet to accommodate modern container ships built to the new guidelines. 950 ft.

How long did the Mississippi river flow backwards?

More than 200 years ago the Mississippi River waters spun in a reverse course for three days, also due to a natural disaster, but not a hurricane. Instead, this was caused by a massive earthquake in the New Madrid seismic zone reaching down into the Mississippi River.

Is the Mississippi flowing backwards?

The fact that the Mississippi River ran backwards after the massive New Madrid earthquake of 1811 is now the stuff of legend, but did you know that it's run backwards at least twice since?

What is the only river that flows backwards?

The Chicago River Actually Flows Backwards.

Do rivers ever change course?

All rivers naturally change their path over time, but this one forms meanders (the technical name for these curves) at an especially fast rate, due to the speed of the water, the amount of sediment in it, and the surrounding landscape.

How much has the Mississippi river moved?

1, it has dropped more than half its original elevation and is 687 feet (209 m) above sea level. From St. Paul to St. Louis, Missouri, the river elevation falls much more slowly and is controlled and managed as a series of pools created by 26 locks and dams.

Did an earthquake changed the course of the Mississippi?

One of the world's most powerful earthquakes changed the course of the Mississippi River in Missouri and created Reelfoot Lake in Tennessee while shaking parts of Arkansas, Kentucky, Illinois and Ohio.

What if the Old River Control Structure fails?

Failure of the Old River Control Structure and the resulting jump of the Mississippi to a new path to the Gulf would be a severe blow to America's economy, robbing New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and the critical industrial corridor between them of the fresh water needed to live and do business.

What is the future of the Mississippi River Delta?

The Mississippi River Delta faces an uncertain future as sea level keeps rising while the land continues to subside. To protect the coastal landscape, communities, and economic future, the State of Louisiana developed a Master Plan in 2007 with technical tools that are used as a framework to assist implementing various restoration and protection projects. In its latest Master Plan draft of 2017, the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority has outlined a $50 billion investment for 120 projects designed to build and maintain coastal Louisiana. These projects are well intended and are normally backed up with scientific data analysis. However, they are all developed under the assumption that the Mississippi River (MR) would remain on its current course, which is artificially maintained through a control structure built in 1963 (a.k.a. the Old River Control Structure, or ORCS) after it was realized that the river attempted to change its course back to its old river channel - the Atchafalaya River (AR). Since the ORCS is in operation of controlling only about 25% of the MR flow into the AR, little attention has been paid to the importance of possible riverbed changes downstream the avulsion node on the MR course switch. As one of the largest alluvial river in the world, the MR avulsed and created a new course every 1,000-1,500 years in the past. From a fluvial geomorphology point of view, alluvial rivers avulse when two conditions are met: 1) a sufficient in-channel aggradation which makes the river poised for an avulsion, and 2) a major flood which triggers realization of the avulsion. In our ongoing study on sediment transport and channel morphology of the lower Mississippi River, we found that the first 30-mile reach downstream the ORCS has been experiencing rapid bed aggradation and channel narrowing in the past three decades. A mega flood could be a triggering point to overpower the man-made ORCS and allow the river finally abandon its current channel – the MR main stem. This is not a desirable path and, for that reason, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will do everything possible to prevent it from happening. However, nature has its own mechanism of choosing river flows, which do not bow to our expectation: the 2016 summer flood in South Louisiana and the recent Oroville Dam crisis in California are just two examples. The MR river flow has been increasing over the past century. The river is projected to further increase its flow volume as global temperature continues to rise and hydrologic cycle intensifies, i.e. evapotranspiration rates will increase and rain storms will become more intense on a warming earth. Additionally, rapid urbanization in the river basin will create conditions that foster the emergence of mega floods. It would be impractical to spend considerable resources for a river delta without assessing the future avulsion risk of the river upstream. This presentation discusses the possibility of a Mississippi River avulsion, its consequences, as well as what assessment data we need to develop rational strategies.

What is the Mississippi Delta?

The Mississippi delta is one of the largest and best studied of global deltas, and like all deltas. The Mississippi rebuilt the modern MRD (Mississippi River delta) across the continental shelf of the northern Gulf of Mexico over the past 7000. years during a period of relative sea-level stasis. Delta formation was enhanced by a hierarchical series of forcing functions acting over different spatial and temporal scales during a period of stable sea level, predictable inputs from its basin, and as an extremely open system with strong interactions among river, delta plain, and the coastal ocean. But within the last century, the MRD has-like many deltas worldwide-also been profoundly altered by humans with respect to hydrology, sediment supply, sea-level rise, and land use that directly affect sustainability as sea-level rise accelerates. Collectively, human actions have tilted the natural balance between land building and land loss in the MRD toward a physical collapse and conversion of over 25% of the deltaic wetland inventory to open water since the 1930s. The state of Louisiana is investing $50. billion in a 50-year coastal master plan (CMP) (revised at 5-year intervals) to reduce flood risk for developed areas and restore prioritized deltaic wetlands to a more self-sustaining and healthy condition. It is believed that both hard structures (levees, floodwalls) and wetlands sustained by "soft" projects (river diversions, marsh nourishment, barrier island maintenance) can work together to reduce risk of future hurricane damage to coastal cities, towns, and industry, while also protecting livelihoods and ways of life built around harvesting natural resources. But the pace of greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change, as well as the inevitable rise in out year energy costs, will make achieving CMP goals ever more challenging and expensive. Regardless of the project portfolios evaluated in the current CMP, the hydrodynamic and ecological modeling underpinning CMP projections indicates that fully implementing the plan will reduce future deltaic land-loss rates by less than 20%. Our analysis shows that the cost of delta restoration is quite sensitive to project type and sequencing. Investment is, for example, front loaded for river diversions and marsh creation but back loaded for most other project types. Repeated evacuations followed by more or less managed retreat will also continue to be necessary for much of the population even if the existing CMP is improved to increase supply of fine-grained sediments to the MRD. The CMP is ecological engineering on a grand scale, but to be successful it must operate in consonance with complex social processes. This will mean living in a much more open system, accepting natural and social limitations, and utilizing the resources of the river more fully.

How long has the Mississippi River changed course?

The Mississippi River has changed course to the Gulf every thousand years or so for about the last 10,000 years. Gravity finds a shorter, steeper path to the Gulf when sediments deposited by the river make the old path higher and flatter. It’s ready to change course again.

What is the effect of floods on the Mississippi River?

The higher the hill, the greater the “head” or force driving the flow. Floods on the Mississippi raise the water level inside the levees and increase this force. Floods are becoming more frequent, longer, and higher — even though average annual rainfall in the Mississippi drainage basin has been almost flat since 1940.

What percentage of Mississippi River flows down the Atchafalaya?

The control structure “stopped time” on the Mississippi River, said Army Corps public affairs officer Ricky Boyett. The Red and Mississippi rivers continue to send 30 percent of their combined flow down the Atchafalaya, while the lower Mississippi claims the remaining 70 percent, just as in the 1950s.

Where is the Army Corps of Engineers battling with nature?

Army Corps of Engineers is battling with the forces of nature. At the confluence of the Mississippi, Atchafalaya and Red rivers, the Corps has erected towering gates that bend the flow of the water.

What would happen if the Mississippi River changed course?

A course change in the Mississippi would severely impact the oil industry, shipping and fisheries industries.

How much material has been dredged at the mouth of the Mississippi River?

According to U.S. Army Corp of Engineer’s Col. Michael Clancy more than 30 million yards of material has been dredge at the mouth of the Mississippi river, an amount that the river replaces in 11 minutes. Photo: Facebook. According to U.S. Army Corp of Engineer ‘s Col. Michael Clancy, New Orleans District Commander, ...

What are the sand bars on the Mississippi River?

The sand bars currently clogging the Mississippi are depositional features of sediment reducing flow power. They are similar to small islands and an important part of the life cycle of the river. These formations continue to form along the river’s path.

How much of the Louisiana Delta has been lost since 1932?

Since 1932 almost two million acres of the Louisiana delta plain has been lost, as the Louisiana Gulf coast has experienced one of the highest rises in sea level over the past century. There is one possible positive effect from the 150-mile course change into the Atchafalaya according to Xu. “The Delta will grow very fast.

Is the Mississippi River correcting the Atchafalaya?

Mississippi River Course to Correct to Atchafalaya According to LSU Professor. The Mississippi River is trying to change course into the its historic Atchafalaya Basin channel accordingDr. Jun Xu, a world-renowned hydrologist and Professor of Hydrology of Louisiana State University’sSchool of Renewable Natural Resource.

Who designed the Old River Control Structure?

When the Old River Control Structure was designed, Hans Albert Einstein, son of Albert Einstein and Professor of Hydrology at the University of California – Berkeley, was a consultant on sedimentation hired by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers.

Is the Mississippi River changing course?

The Mississippi River is trying to change course into the its historic Atchafalaya Basin channel according to Dr. Jun Xu, a world-renowned hydrologist and Professor of Hydrology at Louisiana State University’s School of Renewable Natural Resource, in a recently released video on Bigger Pie Forum. A course correction Xu says is not a matter ...

Popular Posts:

- 1. what is solid and non-solid course

- 2. how long is the umuc cybersecurity course

- 3. what time does marquette park golf course open

- 4. how to do a course without a textbook

- 5. how do i make a course

- 6. how long does the buyer educator course certificant last

- 7. how to stop course hero payment

- 8. how can i prove that my emt course in the state of texas was dot approved?

- 9. why can't i click special course type on amcas

- 10. which of these is not one of hofstede's dimensions of cultural values? course hero