Traditionally, teacher evaluation is conducted by a principal, department head, or teacher evaluator who observes how a teacher handles a class with the help of checklists. Other factors like assessments, lesson plans, daily records, and student outputs are also taken into account.

Full Answer

How is teacher evaluation conducted in the classroom?

Feb 09, 2014 · Research shows that student evaluations often are more positive in courses that are smaller rather than larger and elective rather than required. Also, evaluations are usually more positive in courses in which students tend to do well. If you’re teaching a particularly challenging subject, working your students to their full potential or if you’re a harsh (ok, fair) grader, …

Are course evaluations a good measure of teaching quality?

They’re often seen as the bane of a professor’s existence: student course evaluations. Among the many criticisms that faculty level at such evaluations is that they’re not taken seriously by students, aren’t applied consistently, may be biased and don’t provide meaningful feedback. Guilty on all counts, if they’re designed poorly ...

Why don’t students respond to teacher evaluations in small classes?

Apr 14, 2020 · Course evaluations are directive for both the instructor’s work in and out of the classroom, as well as for the course business as a whole. However, the amount of valuable information you get from the evaluations requires that you know how to read, organize and interpret the responses you have collected. In addition, you also need to know how to use these …

How do student evaluations differ between courses?

Apr 28, 2022 · As you go along with the evaluation, remember to make unbiased, accurate, and consistent judgments based on the learning evidence. Step 2: Engage Teacher Leaders The success of learning is a product of a collaborative effort. All teacher leaders should be actively involved in the process of improving teaching practices.

How do you deal with a bad course evaluation?

- Get past your gut reaction. Anyone who has received negative feedback knows criticism can stir up emotions ranging from disbelief to discouragement. ...

- Consider the context. ...

- Seek teaching advice if you need it. ...

- Get feedback more often. ...

- Show students you care.

How do you respond to a negative teacher evaluation?

- Stay Calm and Don't React Right Away. ...

- “You might want to vent to a colleague about the situation, especially if you feel you had an unfair evaluation. ...

- Take Notes During the Observation Review. ...

- Be Kind to Yourself. ...

- Review the Observation and Comments. ...

- Learn More About the Evaluator.

How do you deal with negative attitudes in the classroom?

- Bring difficult students close to you. Bring badly behaved students close to you. ...

- Talk to them in private. ...

- Be the role model of the behavior you want. ...

- Define right from wrong. ...

- Focus more on rewards than punishments. ...

- Adopt the peer tutor technique. ...

- Try to understand.

Are course evaluations confidential?

What would you do if your school head give you negative feedback on the way you teach?

How do you deal with an unprofessional teacher?

- Address the Behavior with the Teacher. ...

- Get Administration Involved. ...

- Learn to Properly Express Your Own Feelings. ...

- Remove Yourself from the Situation. ...

- Don't Let Go of Your Own Positivity.

How do you respond to a disrespectful student?

- Change your mindset. ...

- Have empathy. ...

- Be consistent with expectations. ...

- Train yourself to not take offense. ...

- Consider skill deficits. ...

- Focus on the relationship. ...

- Ignore what you can ignore.

How should a teacher handle a disruptive student?

- Don't take the disruption personally. Focus on the distraction rather than on the student and don't take disruption personally. ...

- Stay calm. ...

- Decide when you will deal with the situation. ...

- Be polite. ...

- Listen to the student. ...

- Check you understand. ...

- Decide what you're going to do. ...

- Explain your decision to the student.

Can a teacher refuse to teach a violent pupil?

Can teachers see who did course evaluations?

Do professors know who wrote course evaluations?

Do professors see their course evaluations?

What to do if your teaching evaluations are bad?

If the teaching evaluations are really bad, talk to your supervisor. They’ve (probably) observed you throughout the quarter, they are going to see the reviews anyway, and they might in fact have some useful feedback. If the supervisor-talk sounds too intimidating you could approach some other senior colleagues you trust.

Why are student evaluations positive?

Know the facts. Research shows that student evaluations often are more positive in courses that are smaller rather than larger and elective rather than required. Also, evaluations are usually more positive in courses in which students tend to do well. If you’re teaching a particularly challenging subject, working your students to their full potential or if you’re a harsh (ok, fair) grader, chances are some students won’t be thrilled, no matter how good your teaching skills or how much you care.

What does it mean when a teacher has negative student reviews?

Talking about inexperience, negative student reviews are frequently a reflection of insufficient teacher training. If you want to or have to stick with teaching, seek out opportunities for further training. If your department doesn’t provide substantial training to prospective or current TAs, contact other related departments or contact your school’s Office of Instructional Development.

What are the criticisms of faculty evaluations?

Among the many criticisms that faculty level at such evaluations is that they’re not taken seriously by students, aren’t applied consistently, may be biased and don’t provide meaningful feedback. Guilty on all counts, if they’re designed poorly, says Pamela Gravestock, the associate director of the Centre for Teaching Support and Innovation at the University of Toronto. But that doesn’t have to be the case. Done well, they can be both a useful and effective measure of teaching quality, she says.

What makes a teacher effective?

It often gets boiled down to particular characteristics – communication skills, organization . But ultimately what we should be assessing for teacher effectiveness is learning, and course evaluations are limited in their ability to do that. They’re assessing the student’s perception of their learning or their experience of learning in a course, but not whether they’ve actually learned anything. That’s why they should be only one factor when you’re assessing effectiveness.

How many core questions are there on evaluation forms?

Dr. Gravestock: We have eight core institutional questions that appear on all evaluation forms. And then faculties and departments can add their own that reflect their contexts, needs and interests.

Do students respond to a course if it's tough?

Dr. Gravestock: There have been a fair number of studies with regard to the perception that students will provide more favourable feedback when the course is easy. But there have been studies that have countered that claim. Students will respond favourably to a course, even if it’s tough, if they knew it was going to be tough. If the expectations of the instructor are made clear at the outset of a course, and students understand what is expected of them, they won’t necessarily evaluate the instructor harshly.

Do you have to fill out an evaluation for every course?

Dr. Gravestock: It’s required that an evaluation be administered for every course, but it’s not required that an individual student fill it out.

Can students provide feedback on a course?

Dr. Gravestock: Yes and no. There are definitely certain things that students can provide feedback on, but there are also things that students are not necessarily in a position to provide feedback on. An example of the latter is a question that appears on most course evaluations, asking students to comment on the instructor’s knowledge ...

Is the question "general questions about the instructor's effectiveness" the right question?

Dr. Gravestock: I would relate that back in part to the instrument itself. Often the questions are not the right questions. General questions about the instructor’s effectiveness aren’t going to tell you what’s going on. Also, faculty are often just given this information and no one guides them through it. Educational developers are really well-positioned to help instructors in interpreting the data and figuring out next steps – a plug for my profession!

What is the best way to interpret a course evaluation?

First: Good interpretations start with the evaluation form itself. The best course evaluation forms contain few, well-formulated questions that have been carefully selected. Only when the right questions are in place will you get good answers that you can interpret and use to further develop your courses.

What is holding a course without asking for evaluation?

Holding courses without asking your participants for course evaluations is a bit like driving a car without a steering wheel. Course evaluations are directive for both the instructor’s work in and out of the classroom, as well as for the course business as a whole. However, the amount of valuable information you get from ...

Why do people think of answering random questions?

People can think of answering random answers to get the evaluation completed as quickly as possible.

What does exploring the different values that your dataset gives you?

By exploring the different values that your dataset gives you, you will form a more complete picture of what kind of experience your participants have gained from the course they have attended.

How to analyze open questions?

One of the most common ways of analyzing open questions is to create word clouds. This is a visual representation of the most commonly used words and phrases in your responses. They often look like this:

What does "most typical" mean?

Definition: The value of a number material that is “most typical”, ie the number that occurs most times.

What is median in table?

Definition: The median is “in the middle of the table” if the results are set in descending (or ascending) order.

What is teacher evaluation?

Teacher evaluation is the standardized process of rating and assessing the teaching effectiveness of educators. Teacher performance evaluations aim to help promote a better learning experience for students and foster professional growth for educators. iAuditor for teacher evaluation.

Why is teacher evaluation important?

As an evaluator, your role will have a huge impact in helping educators step up their quality of teaching and improve student learning.

What is an OTES?

OTES (Ohio Teacher Evaluation System) was created in response to House Bill 1 in 2009, which directed the Educator Standards Board to recommend model evaluation systems for teachers and principals. OTES uses formal observations, classroom walkthroughs, and a teacher performance evaluation rubric with 3 sections:

What is the RIIC evaluation system?

Like RISE, the RIIC (Rhode Island Innovation Consortium) Evaluation System is adapted from Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching. Aside from impact on student growth and achievement, the RIIC Evaluation System relies on other measures of educator effectiveness, such as these 4 standards:

What is a measure in GTL?

Measures are the medium through which the teacher evaluation will be conducted. The GTL Center recommends selecting multiple measures such as:

What should be the structure of a teacher evaluation system?

The structure of a teacher evaluation system should be based on the designated levels of teacher performance (e.g., developing, proficient, exemplary) and the frequency of evaluations, which is different for each measure. Moreover, the weight or percentage of each measure in relation to the overall teacher rating will affect how the teacher evaluation system should be structured.

What is the most important part of the teacher evaluation framework?

According to Danielson, the most important part of the teacher evaluation framework is the 3rd domain “Instruction.” Students should be intellectually involved in the learning process through activities. As you go along with the evaluation, remember to make unbiased, accurate, and consistent judgments based on the learning evidence.

How to assess the effectiveness of teaching and courses?

There are many ways to assess the effectiveness of teaching and courses, including feedback from students, input from colleagues, and self-reflection. No single method of evaluation offers a complete view. This page describes the end-term student feedback survey and offers recommendations for managing it.

What is Stanford course feedback?

At Stanford, student course feedback can provide insight into what is working well and suggest ways to develop your teaching strategies and promote student learning, particularly in relation to the specific learning goals you are working to achieve.

When does the end term survey open?

The end-term student feedback survey, often referred to as the “course evaluations”, opens in the last week of instruction each quarter for two weeks :

What is the function of evaluation?

There are two competing functions of the evaluation. The first is to give you feedback for course improvement, and the second is to assess performance. What the students might think is constructive feedback might be seen as a negative critique by those not in the classroom.

Why do I avoid doing evaluations?

I try to avoid doing evaluations when students are more anxious about their grade, like on the cusp of an exam or when I return graded assignments. When I hand out the very helpful final exam review sheet, which causes relief, then I might do evaluations.

What is the classic strategy for a term?

A classic strategy is to start out the term with extreme rigor, and lessen up as time goes on. I don’t do this, at least not intentionally, but I don’t think it’s a bad idea as long as you finish with high expectations. In any circumstance, I imagine it would be disaster to increase the perceived level of difficulty during the term.

What does PTE stand for in a university?

My university aptly calls these forms by their acronym, “PTE”: Perceived Teaching Effectiveness. Note the word: “perceived.” Actual effectiveness is moot.

Does weather affect evaluation?

If you are a younger woman, you have to reckon with a distinct set of challenges and biases. If the weather is better out, you might get better evaluations, too . So, don’t feel bad about doing things to help your scores, even if they aren’t connected to teaching quality.

Do you bring in special treats on evaluation day?

I don’t bring in special treats on the day I administer evaluations. At least with my style, my students would find it cloying, and they wouldn’t appreciate a cheap bribe attempt. Once in a long while, I may bring in donuts or something else like that, but never on evaluation day.

What is the real goal of a single course evaluation?

The real goal is the improvement of student learning, holistically and over time. Single course evaluation results are just small pieces of a larger picture and should be viewed in that context, rather than in isolation. (18)

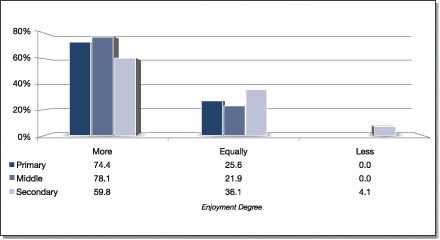

Why were instructor reports redesigned?

In step with changes to the course feedback form, the instructor reports were also redesigned to move away from reliance on averages and direct attention to the distribution of scores , enabling instructors to make more informed judgements about the range of student responses (Fig. 1).

What is section feedback?

The section feedback form is used to evaluate instructors in course sections, such as labs and discussion sections, including TAs , CAs, and Teaching Fellows. The current section feedback form is based on the section leader evaluation form, used before Autumn 2015-2016, but incorporates several changes. Bearing in mind that these results can often be part of an instructor’s teaching portfolio and used in job applications, the section form is designed to elicit useful feedback for the instructor specifically. The section form includes an extensive question bank from which the instructor can select items that specifically reflect elements of their teaching situation and style, and there are several opportunities for students to provide detailed, open-ended responses on aspects of the instructor’s teaching that were most helpful or offer potential for improvement. This gives wide scope to students’ qualitative feedback for those TA and CA instructors who may be contemplating a teaching career.

What is Stanford's approach to teaching?

The Stanford approach: using feedback to improve teaching and learning. End-term course feedback began at Stanford as a student initiative in the late 1950s 18, when a student publication, The Scratch Sheet, first published editorial descriptions of courses.

What is student response?

Student responses, focused on their experience of the course and its goals rather than individual instructors, can productively inform the growth of instructors and their pedagogical approaches. To reflect this, the current course form is shorter, structured by student’s experience of the course, and customizable.

What are the goals of instructors?

Instructors have the freedom to craft learning goals that reflect their own goals and models for student learning, from discrete units of skill or competency to outcomes such as informed and deepened appreciation of the field or the ability to synthesize viewpoints into an argument.

How are ratings biased?

Ratings can be biased by a number of variables such as an instructor’s gender, perceived attractiveness, ethnicity, and race. Evidence also suggests that course characteristics such as class size and type (core curriculum versus elective) affect SETs.

How to tell if an instructor is 4.2?

There is no way to tell from the averages alone, even if response rates were perfect. Comparing averages in this way ignores instructor-to-instructor and semester-to-semester variability. If all other instructors get an average of exactly 4.5 when they teach the course, 4.2 would be atypically low. On the other hand, if other instructors get 6s half the time and 3s the other half of the time, 4.2 is almost exactly in the middle of the distribution. The variability of scores across instructors and semesters matters, just as the variability of scores within a class matters. Even if evaluation scores could be taken at face value, the mere fact that one instructor’s average rating is above or below the mean for the department says very little. Averages paint a very incomplete picture. It would be far better to report the distribution of scores for instructors and for courses: the percentage of ratings that fall in each category (1–7) and a bar chart of those percentages.

What about qualitative responses, rather than numerical ratings?

What about qualitative responses, rather than numerical ratings? Students are well situated to comment about their experience of the course factors that influence teaching effectiveness, such as the instructor’s audibility, legibility, and availability outside class. [10]

What is merit review in Berkeley?

As noted above, Berkeley’s merit review process invites reporting and comparing averages of scores, for instance, comparing an instructor’s average scores to the departmental average. Averaging student evaluation scores makes little sense, as a matter of statistics. It presumes that the difference between 3 and 4 means the same thing as the difference between 6 and 7. It presumes that the difference between 3 and 4 means the same thing to different students. It presumes that 5 means the same things to different students in different courses. It presumes that a 4 “balances” a 6 to make two 5s. For teaching evaluations, there’s no reason any of those things should be true. [7]

What is effectiveness rating?

Effectiveness ratings are what statisticians call an “ordinal categorical” variable: The ratings fall in categories with a natural order (7 is better than 6 is better than … is better than 1), but the numbers 1, 2, …, 7 are really labels of categories, not quantities of anything.

What does it mean when a response rate is lower?

The lower the response rate, the less representative of the overall class the responders might be. Treating the responders as if they are representative of the entire class is a statistical blunder.

What is quantitative student ratings?

Quantitative student ratings of teaching are the most common method to evaluate teaching. [1] . De facto, they define “effective teaching” for many purposes, including faculty promotions. They are popular partly because the measurement is easy: Students fill out forms.

Is online teaching evaluations a survey?

Online teaching evaluations may become (at departments’ option) the primary survey method at Berkeley this year. This raises additional concerns. For instance, the availability of data in electronic form invites comparisons across courses, instructors, and departments; such comparisons are often inappropriate, as we discuss below. There also might be systematic differences between paper-based and online evaluations, which could make it difficult to compare ratings across the “discontinuity. [3]

Popular Posts:

- 1. if i could create a high school course what would it be

- 2. which course is very easy

- 3. how much is a digital marketing course

- 4. under a commission incentive system which is the basis for individuals compensation course hero

- 5. how much does a head pro at a golf course make

- 6. what learning and growth are you aware of at this point in the diversity course ?

- 7. what to do if uic bookstore list course as null

- 8. when did leif ericson get blown off course

- 9. which renal change is found in older adults course hero

- 10. what should you consider when selecting a firewall for your organization? course hero